Wednesday, December 27, 2006

Monday, December 25, 2006

NATALE . . .

“The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light; upon those who dwelt in the land of gloom a light has shone.

You have brought them abundant joy and great rejoicing, as they rejoice before you as at the harvest, as men make merry when dividing spoils.

For the yoke that burdened them, the pole on their shoulder, and the rod of their taskmaster you have smashed, as on the day of Midian.

For every boot that tramped in battle, every cloak rolled in blood, will be burned as fuel for flames.

For a child is born to us, a son is given us; upon his shoulder dominion rests. They name him Wonder-Counselor, God-Hero, Father-Forever, Prince of Peace.”

(Isaiah 9:2 – 9:6)

“In the beginning was the Word,

and the Word was with God,

and the Word was God.

He was in the beginning with God.

All things came to be through him,

and without him nothing came to be.

What came to be through him was life,

and this life was the light of the human race;

the light shines in the darkness,

and the darkness has not overcome it.”

(John 1:1 – 1:5)

Saturday, December 09, 2006

A Simple Question . . .

“What is the meaning of life? That was all – a simple question; one that tended to close in on one with years. The great revelation had never come. The great revelation perhaps never did come. Instead there were little daily miracles, illuminations, matches struck unexpectedly in the dark . . .”

(Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse)

Tuesday, December 05, 2006

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Sunday, November 26, 2006

poetree

bears a tree with bare branches stems from parched bark and twisted twigs leaves fallen leaves to winter wind roots the sky in dry earth sprouts within and blooms without flowers the seeds of trees . . .

Copyright © 2006 Marco Alexandre de Oliveira

On the Edge of Happiness . . .

“It was his fate, his peculiarity, whether he wished it or not, to come out thus on a spit of land which the sea is slowly eating away, and there to stand, like a desolate sea-bird, alone. It was his power, his gift, suddenly to shed all superfluities, to shrink and diminish so that he looked barer and felt sparer, even physically, yet lost none of his intensity of mind, and so to stand on his little ledge facing the dark of human ignorance, how we know nothing and the sea eats away the ground we stand on – that was his fate, his gift.”

“He turned from the sight of human ignorance and human fate and the sea eating the ground we stand on, which, had he been able to contemplate it fixedly might have led to something; and found consolation in trifles so slight compared with the august theme just now before him that he was disposed to slur the comfort over, to deprecate it, as if to be caught happy in a world of misery was for an honest man the most despicable of crimes. It was true; he was for the most part happy. . . .”

(Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse)

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

A Time to Rhyme

only herds

of lonely words –

a faceless multitude,

a baseless solitude –

traverse in verse

the pages of the ages.

names in frames – like you and I – as real and ideal as earth and sky, wander around and wonder about the signs they signify, or the nature of their stature, from their birth until they die; for still the years still transform begotten forms until appearances disappear along with long forgotten formal norms of characterization, characterized by characters in action . . . of course, perhaps this so-called individual discourse, per se, after all never original, is always and ever a source of hype, a perverse type of blend adverse to trends and style; while meanwhile seen as a genius of a genus, is such, as such, in a sense, in essence, a nonsense, since this revolution of resolution is the expression of impressions of the same rules from whence it came; hence fools become tools of a tragic logic as subjects object to a language of bondage: “objects subject to the bondage of language!” the former insists, the latter resists – letters in fetters digress, impede progress – the stampede tramples over borders of thought, these orders that ought to contain and restrain remain what sustain a predestined ambition: to end and transcend a questioned condition, a unique and oblique obsession reflective of a perspective of oppression . . . finally a finale – herds of words are heard! a leader elects to select a reader to free the story from history, and (re)present the advent of the moment, to see all class as allegory, and pass the time(s) with rhyme(s). . . .

Copyright © 2006 Marco Alexandre de Oliveira

On Sesame and Lilies . . .

“And be sure also, if the writer is worth anything, that you will not get at his meaning all at once; – nay, that at his whole meaning you will not for a long time arrive in any wise. Not that he does not say what he means, and in strong words too; but he cannot say it all; and what is more strange, will not, but in a hidden way and in parables, in order that he may be sure you want it. I cannot quite see the reason of this, nor analyze that cruel reticence in the breasts of wise men which makes them always hide their deeper thought. They do not give it you by way of help, but of reward; and will make themselves sure that you deserve it before they allow you to reach it. . . ."

(John Ruskin, Sesame and Lilies)

Saturday, November 18, 2006

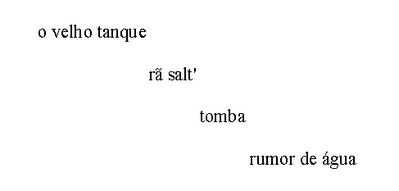

Velha lagoa / Old pond . . .

O velho tanque / The old pond . . .

Thursday, November 16, 2006

Impressions on Art . . .

“And what other means were open to me than the creation of a work of art?”

“Thus I had already reached the conclusion that we are in no wise free in the presence of a work of art, that we do not create it as we please but that it pre-exists in us and we are compelled as though it were a law of nature to discover it because it is at once hidden from us and necessary. But is not that discovery, which art may enable us to make, most precious to us, a discovery of that which for most of us remains for ever unknown, our true life, reality as we have ourselves felt it and which differs so much from that which we had believed that we are filled with delight when chance brings us an authentic revelation of it?”

“The grandeur of veritable art . . . is to recapture, to lay hold of, to make one with ourselves that reality far removed from the one we live in, from which we separate ourselves more and more as the knowledge which we substitute for it acquires a greater solidity and impermeability, a reality we run the risk of never knowing before we die but which is our real, our true life at last revealed and illumined, the only life which is really lived and which in one sense lives at every moment in all men as well as in the artist. But they do not see it because they do not seek to illuminate it. And thus their past is encumbered with innumerable “negatives” which remain useless because the intelligence has not “developed” them. To lay hold of our life; and also the life of others; for a writer’s style and also a painter’s are matters not of technique but of vision. It is the revelation, impossible by direct and conscious means, of the qualitative difference there is in the way in which we look at the world, a difference which, without art, would remain for ever each man’s personal secret. By art alone we are able to get outside ourselves, to know what another sees of this universe which for him is not ours, the landscapes of which would remain as unknown to us as those of the moon. Thanks to art, instead of seeing one world, our own, we see it multiplied and as many original artists as there are, so many worlds are at our disposal, differing more widely from each other than those which roll round the infinite and which . . . send us their unique rays many centuries after the hearth from which they emanate is extinguished. This labour of the artist to discover a means of apprehending beneath matter and experience, beneath words, something different from their appearance . . . this complex art is precisely the only living art. It alone expresses for others and makes us see, our own life, that life which cannot observe itself, the outer forms of which, when observed, need to be interpreted and often read upside down, in order to be laboriously deciphered.”

Marcel Proust, Time Regained (Vol. 7 of Remembrance of Things Past. Trans. Stephen Hudson)

A Book of Symbols . . .

“I was attempting to concentrate my mind on a compelling image, a cloud, a triangle, a belfry, a flower, a pebble, believing that there was perhaps something else under those symbols I ought to try to discover, a thought which these objects were expressing in the manner of hieroglyphic characters which one might imagine only represented material objects. Doubtless such deciphering was difficult, but it alone could yield some part of the truth.”

“That book of unknown signs within me (signs in relief it seemed, for my concentrated attention, as it explored my unconscious in its search, struck against them, circled round them like a diver sounding) no one could help me read by any rule, for its reading consists in an act of creation in which no one can take our place and in which no one can collaborate . . . That book which is the most arduous of all to decipher is the only one which reality has dictated, the only one printed within us by reality itself. Whatever idea life has left in us, its material shape, mark of the impression it has made on us, is still the necessary pledge of its truth . . . Our only book is that one not made by ourselves whose characters are already imaged . . . That which we have not been forced to decipher, to clarify by our own personal effort, that which was made clear before, is not ours. Only that issues from ourselves which we ourselves extract from the darkness within ourselves and which is unknown to others. And as art exactly recomposes life, an atmosphere of poetry surrounds those truths within ourselves to which we attain, the sweetness of a mystery which is but the twilight through which we have passed.”

“I perceived that to express those impressions, to write that essential book, which as the only true one, a great writer does not, in the current meaning of the word, invent it, but, since it exists already in each one of us, interprets it. The duty and the task of a writer are those of an interpreter.”

Marcel Proust, Time Regained (Vol. 7 of Remembrance of Things Past. Trans. Stephen Hudson)

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

Doors to Nowhere . . .

“But it is sometimes just at the moment when we think that everything is lost that the intimation arrives which may save us; one has knocked at all the doors which lead nowhere, and then one stumbles without knowing it on the only door through which one can enter – which one might have sought in vain for a hundred years – and it opens of its own accord.”

Marcel Proust, Time Regained. (Vol. 7 of Remembrance of Things Past. Trans. Moncrieff and Kilmartin)

Monday, November 13, 2006

In Search of Lost Hope . . .

"How often . . . did I reflect on my lack of qualification for a literary career, and that I must abandon all hope of ever becoming a famous author. The regret that I felt for this, while I lingered alone to dream for a little by myself, made me suffer so acutely that, in order not to feel it, my mind of its own accord, by a sort of inhibition in the instant of pain, ceased entirely to think of verse-making, of fiction, of the poetic future on which my want of talent precluded me from counting. Then, quite apart from all those literary preoccupations, and without definite attachment to anything, suddenly a roof, a gleam of sunlight reflected from a stone, the smell of a road would make me stop still, to enjoy the special pleasure that each of them gave me, and also because they appeared to be concealing, beneath what my eyes could see, something which they invited me to approach and seize from them, but which, despite all my efforts, I never managed to discover. As I felt that the mysterious object was to be found in them, I would stand there in front of them, motionless, gazing, breathing, endeavouring to penetrate with my mind beyond the thing seen or smelt. And if I had then . . . to proceed on my way, I would still seek to recover my sense of them by closing my eyes; I would concentrate upon recalling exactly the line of the roof, the colour of the stone, which, without my being able to understand why, had seemed to me to be teeming, ready to open, to yield up to me the secret treasure of which they were themselves no more than the outer coverings. It was certainly not any impression of this kind that could or would restore the hope I had lost of succeeding one day in becoming an author and poet, for each of them was associated with some material object devoid of any intellectual value, and suggesting no abstract truth. But at least they gave me an unreasoning pleasure, the illusion of a sort of fecundity of mind; and in that way distracted me from the tedium, from the sense of my own impotence which I had felt whenever I had sought a philosophic theme for some great literary work . . . ."

[Swann's Way (Vol. 1 of Remembrance of Things Past) by Marcel Proust, translated from the French by C. K. Scott Moncrieff (1922)]

http://www.authorama.com/remembrance-of-things-past-4.html

Thursday, November 09, 2006

Tuesday, November 07, 2006

ut pictura poesis

ver no poema o que dizer na pintura

da figura a compor:

o inverso do universo em verso

Copyright © 2006 Marco Alexandre de Oliveira

Sunday, November 05, 2006

On Reading (Proust) . . .

“And then my thoughts, did not they form a similar sort of hiding-hole, in the depths of which I felt that I could bury myself and remain invisible even when I was looking at what went on outside? When I saw any external object, my consciousness that I was seeing it would remain between me and it, enclosing it in a slender, incorporeal outline which prevented me from ever coming directly in contact with the material form; for it would volatilise itself in some way before I could touch it . . . Upon the sort of screen, patterned with different states and impressions, which my consciousness would quietly unfold while I was reading, and which ranged from the most deeply hidden aspirations of my heart to the wholly external view of the horizon spread out before my eyes at the foot of the garden, what was from the first the most permanent and the most intimate part of me, the lever whose incessant movements controlled all the rest, was my belief in the philosophic richness and beauty of the book I was reading, and my desire to appropriate these to myself, whatever the book might be. For even if I had purchased it . . . I should have noticed and bought it there simply because I had recognised it as a book which had been well spoken of, in my hearing, by the school-master or the school-friend who, at that particular time, seemed to me to be entrusted with the secret of Truth and Beauty, things half-felt by me, half-incomprehensible, the full understanding of which was the vague but permanent object of my thoughts.”

“Next to this central belief, which, while I was reading, would be constantly a motion from my inner self to the outer world, towards the discovery of Truth, came the emotions aroused in me by the action in which I would be taking part, for these afternoons were crammed with more dramatic and sensational events than occur, often, in a whole lifetime. These were the events which took place in the book I was reading . . .But none of the feelings which the joys or misfortunes of a ‘real’ person awaken in us can be awakened except through a mental picture of those joys or misfortunes; and the ingenuity of the first novelist lay in his understanding that, as the picture was the one essential element in the complicated structure of our emotions, so that simplification of it which consisted in the suppression, pure and simple, of ‘real’ people would be a decided improvement. A ‘real’ person, profoundly as we may sympathise with him, is in a great measure perceptible only through our senses, that is to say, he remains opaque, offers a dead weight which our sensibilities have not the strength to lift . . .The novelist’s happy discovery was to think of substituting for those opaque sections, impenetrable by the human spirit, their equivalent in immaterial sections, things, that is, which the spirit can assimilate to itself. After which it matters not that the actions, the feelings of this new order of creatures appear to us in the guise of truth, since we have made them our own, since it is in ourselves that they are happening, that they are holding in thrall, while we turn over, feverishly, the pages of the book, our quickened breath and staring eyes. And once the novelist has brought us to that state, in which, as in all purely mental states, every emotion is multiplied ten-fold, into which his book comes to disturb us as might a dream, but a dream more lucid, and of a more lasting impression than those which come to us in sleep; why, then, for the space of an hour he sets free within us all the joys and sorrows in the world, a few of which, only, we should have to spend years of our actual life in getting to know, and the keenest, the most intense of which would never have been revealed to us because the slow course of their development stops our perception of them. It is the same in life; the heart changes, and that is our worst misfortune; but we learn of it only from reading or by imagination; for in reality its alteration, like that of certain natural phenomena, is so gradual that, even if we are able to distinguish, successively, each of its different states, we are still spared the actual sensation of change.”

“Had my parents allowed me, when I read a book, to pay a visit to the country it described, I should have felt that I was making an enormous advance towards the ultimate conquest of truth. For even if we have the sensation of being always enveloped in, surrounded by our own soul, still it does not seem a fixed and immovable prison; rather do we seem to be borne away with it, and perpetually struggling to pass beyond it, to break out into the world, with a perpetual discouragement as we hear endlessly, all around us, that unvarying sound which is no echo from without, but the resonance of a vibration from within. We try to discover in things, endeared to us on that account, the spiritual glamour which we ourselves have cast upon them; we are disillusioned, and learn that they are in themselves barren and devoid of the charm which they owed, in our minds, to the association of certain ideas; sometimes we mobilise all our spiritual forces in a glittering array so as to influence and subjugate other human beings who, as we very well know, are situated outside ourselves, where we can never reach them . . . .”

[Swann's Way (Vol. 1 of Remembrance of Things Past) by Marcel Proust, translated from the French by C. K. Scott Moncrieff (1922)]

Monday, October 30, 2006

valeu . . .

ontem morreu

um puto poeta

desgraçado

. . .

valeu

! ? !

Copyright © 2006 Marco Alexandre de Oliveira

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

On I-CON . . .

The “I” (re)presents a presence as the (re)presentation of an absence. Being is (re)presented as being present being absent. The presence of absence (re)presents an identity of difference, a being different being identical to oneself . . .

Indifferent in difference or indifference, “I” is (not) a self contra other, a self contra itself. Itself a self in itself, the other is the selfless other self. Or in other words of another:

I “cannot be itself unless it stands against what is not” I; not-I “is needed to make” I I, “which means that” not-I “is in”

The “I” is thereby a con for a conartist self. Autopoiesis: auto (self) creation. You see, I see a self itself as being other than itself being itself. We see “I see” as a seeing itself unseen. While, meanwhile, the blind “I” (eye) sees a prism (prison) of colors. Unseen colors are seen. The “I” is bound beyond bounds beforeverafterwords, and free . . .

“I” is a vision. “I” is an illusion. “I” is illusivision . . .

“I” is the “I-con.”

(gringocarioca, “On I-con”)

Tuesday, October 24, 2006

The Art of Success and Failure . . .

“Nothing is more strange in art than the way that chance and materials seem to favour you, when once you have thoroughly conquered them. Make yourself quite independent of chance, get your result in spite of it, and from that day forward all things will somehow fall as you would have them.”

“Still, do not be discouraged if you find that you have chosen ill, and that the subject overmasters you. It is much better that it should, than that you should think you had entirely mastered it. But at first, and even for some time, you must be prepared for very discomfortable failure; which, nevertheless, will not be without some wholesome result.”

“When you have practised for a little time from such of these subjects as may be accessible to you, you will certainly find difficulties arising which will make you wish more than ever for a master’s help: these difficulties will vary according to the character of your own mind (one question occurring to one person, and one to another), so that it is impossible to anticipate them all . . . you must be content to work on, in good hope that Nature will, in her own time, interpret to you much for herself; that farther experience on your own part will make some difficulties disappear; and that others will be removed by the occasional observation of such artists’ work as may come in your way.”

(John Ruskin, The Elements of Drawing)

On Handling, Handbooks, and Hands . . .

“But no natural object exists which does not involve in some part or parts of it this inimitableness, this mystery of quantity, which needs the peculiarity of handling and trick of touch to express it completely . . . although methods and dexterities of handling are wholly useless if you have not gained first the thorough knowledge of the thing . . . yet having once got this power over decisive form, you may safely – and must, in order to perfection of work – carry out your knowledge by every aid of method and dexterity of hand”

“It is one of the worst errors of this age to try to know and to see too much: the men who seem to know everything, never in reality know anything rightly. Beware of handbook knowledge.”

“You must stop that hand of yours, however painfully; make it understand that it is not to have its own way anymore, that it shall never more slip from one touch to another without orders; otherwise it is not you who are the master, but your fingers.”

(John Ruskin, The Elements of Drawing)

Why? Because!

“the aspects of things are so subtle and confused that they cannot in general be explained; and in the endeavor to explain some, we are sure to lose sight of others, while the natural over-estimate of the importance of those on which the attention is fixed causes us to exaggerate them . . . The best scholar is he whose eye is so keen as to see at once how the thing looks, and who need not therefore trouble himself with any reasons why it looks so”

(John Ruskin, The Elements of Drawing)

Monday, October 16, 2006

An old haiku/ Um velho haicai . . .

an old haiku –

a frog leaps

the sound of Bashô

ai! velho haicai –

uma solta rã salta

o som de Bashô

Copyright © 2006 Marco Alexandre de Oliveira

Thursday, October 12, 2006

The Bible According to Proust . . .

“It is only when certain periods of our lives have come to a close forever, when, even during the hours in which power and freedom seem to have been given to us, we are forbidden to reopen their doors furtively, it is when we are incapable of placing ourselves again, even for an instant, in our former state, it is only then that we refuse to believe that such things might have been entirely abolished. We can no longer sing of them, having ignored the wise warning of Goethe that there is poetry only in those things which one still feels. But unable to rekindle the flames of the past, we want at least to gather its ashes. Lacking a resurrection we can no longer bring about, with the cold memory we have kept of those things – the memory of facts telling us, ‘you were thus,’ without permitting us to become thus again, affirming to us the reality of a lost paradise instead of giving it back to us through recollection – we wish at least to describe it and to establish its knowledge.”

(Marcel Proust, “Preface to La Bible d’Amiens”)

Wednesday, October 11, 2006

retro-garde . . .

retro-garde

retro-garde, avant-passé:

nay! a place to play today

Remembrance of Things Past . . .

“I feel that there is much to be said for the Celtic belief that the souls of those whom we have lost are held captive in some inferior being, in an animal, in a plant, in some inanimate object, and thus effectively lost to us until the day (which to many never comes) when we happen to pass by the tree or to obtain possession of the object which forms their prison. Then they start and tremble, they call us by our name, and as soon as we have recognised their voice the spell is broken. Delivered by us, they have overcome death and return to share our life.

And so it is with our own past. It is a labour in vain to attempt to recapture it: all the efforts of our intellect must prove futile. The past is hidden somewhere outside the realm, beyond the reach of intellect, in some material object (in the sensation which that material object will give us) of which we have no inkling. And it depends on chance whether or not we come upon this object before we ourselves must die.”

(Marcel Proust, A la recherche du temps perdu. Trans. C. K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin)

On Conceptions and Compositions . . .

"But then, even in the most insignificant details of our daily life, none of us can be said to constitute a material whole, which is identical for everyone, and need only be turned up like a page in an account-book or the record of a will; our social personality is a creation of the thoughts of other people. Even the simple act which we describe as 'seeing someone we know' is to some extent an intellectual process. We pack the physical outline of the person we see with all the notions we have already formed about him, and in the total picture of him which we compose in our minds those notions have certainly the principal place. In the end they come to fill out so completely the curve of his cheeks, to follow so exactly the line of his nose, they blend so harmoniously in the sound of his voice as if it were no more than a transparent envelope, that each time we see the face or hear the voice it is these notions which we recognise and to which we listen."

(Marcel Proust, A la recherche du temps perdu. Trans. C. K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin)

Thursday, October 05, 2006

In Search of Lost Identity . . .

". . . when I awoke in the middle of the night, not knowing where I was, I could not even be sure at first who I was; I had only the most rudimentary sense of existence . . . I was more destitute than the cave-dweller; but then the memory . . . would come like a rope let down from heaven to draw me up out of the abyss of not-being, from which I should have never escaped by myself"

"I . . . examine my own mind. It alone can discover the truth. But how? What an abyss of uncertainty, whenever the mind feels overtaken by itself; when it, the seeker, is at the same time the dark region through which it must go seeking and where all its equipment will avail it nothing. Seek? More than that: create. It is face to face with something which does not yet exist, to which it alone can give reality and substance, which it alone can bring into the light of day."

(Marcel Proust, A la recherche du temps perdu. Trans. C. K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin)

Friday, September 29, 2006

On Servitude and Freedom . . .

“Therefore, this voluntary servitude is the beginning of freedom . . . We are free in life, but subject to purpose: the sophism of freedom of indifference was picked apart long ago. The writer who constantly creates a void in his mind, thinking to free it from any external influence in order to be sure of remaining individual, yields unwittingly to a sophism just as naïve. Actually the only times when we truly have all our powers of mind are those when we do not believe ourselves to be acting with independence, when we do not arbitrarily choose the goal of our efforts. The subject of the novelist, the vision of the poet, the truth of the philosopher are imposed on them in a manner almost inevitable, exterior, so to speak, to their thought. And it is by subjecting his mind to the expression of this vision and to the approach of this truth that the artist becomes truly himself.”

(Marcel Proust, “Preface to La Bible d’Amiens”)

Forget it ! ? !

“It is for the fish that the trap exists; once you’ve got the fish, you forget the trap. It is for the hare that the snare exists; once you’ve got the hare, you forget the snare. It is for the meaning that the word exists; once you’ve got the meaning, you forget the word. Where can I find a man who will forget words so that I can have a word with him?”

(Chuang Tzu, “Wai Wu” [External things]. Trans. Zhang Longxi)

“My propositions serve as elucidations in the following way: anyone who understands me eventually recognizes them as nonsensical, when he has used them – as steps – to climb up beyond them. (He must, so to speak, throw away the ladder after he has climbed up it.)

He must transcend these propositions, and then he will see the world aright.

What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.”

(Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus)

Monday, September 25, 2006

A Concrete “Medium for Poetry”

“Metaphor, the revealer of nature, is the very substance of poetry. The known interprets the obscure, the universe is alive with myth. The beauty and freedom of the observed world furnish a model, and life is pregnant with art.”

“Art and poetry deal with the concrete of nature . . . Poetry is finer than prose because it gives us more concrete truth in the same compass of words. Metaphor, its chief device, is at once the substance of nature and language. Poetry only does consciously what the primitive races did unconsciously. The chief work of literary men in dealing with language, and of poets especially, lies in feeling back along the ancient lines of advance. He must do this so that he may keep his words enriched by all their subtle undertones of meaning. The original metaphors stand as a kind of luminous background, giving color and vitality, forcing them closer to the concreteness of natural processes . . . For these reasons poetry was the earliest of the world arts; poetry, language and the care of myth grew up together.”

“With us, the poet is the only one for whom the accumulated treasures of the race-words are real and active. Poetic language is always vibrant with fold on fold of overtones, and with natural affinities . . .”

“The more concretely and vividly we express the interactions of things the better the poetry . . . Poetic thought works by suggestion, crowding maximum meaning into the single phrase pregnant, charged, and luminous from within.”

“The poet can never see too much or feel too much . . . The prehistoric poets who created language discovered the whole harmonious framework of nature, they sang out her processes in their hymns . . . Thus in all poetry, a word is like a sun, with its corona and chromosphere; words crowd upon words, and enwrap each other in their luminous envelopes until sentences become clear, continuous light-bands.”

(Ernest Fenollosa, “The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry,” Ed. Ezra Pound)

Thursday, September 21, 2006

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

Ruskin's Tower of Babble?

“It is that life of custom and accident in which many of us pass much of our time in the world; that life in which we do what we have not purposed, and speak what we do not mean, and assent to what we do not understand; . . . with all the efforts the best men make, much of their being passes in a kind of dream, in which they indeed move, and play their parts sufficiently, to the eyes of their fellow dreamers, but have no clear consciousness of what is around them, or within them; blind to the one, insensible to the other . . .”

“I do not know of any sensation more exquisite than the discovering of the evidence of this magnificent struggle into independent existence; the detection of the borrowed thoughts, nay, the finding of the actual blocks and stones carved by other hands of other ages, wrought into the new walls, with a new expression and purpose given to them . . .”

“The ambition of the old Babel builders was well directed for this world: there are but two strong conquerors of the forgetfulness of men, Poetry and Architecture; and the latter in some sort includes the former, and is mightier in its reality: it is well to have, not only what men have thought and felt, but what their hands have handled, and their strength wrought, and their eyes beheld, all the days of their life.”

Friday, September 15, 2006

tão alone . . .

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

obscure clarifications . . .

"Despite its communicative efficacy, 'transparency' is not a characteristic or quality of poetic language. Transparency is rather ideal for the communication of information, in which 'A' wishes to communicate a preconceived 'message' to 'B.' Here language is 'used' or 'utilized' (perhaps against its will) in a subservient manner or tone. Language enslaved or oppressed by abstract(ed) logic, reason(s), or ideas is not free to (re)create itself in the very act of 'poiesis' . . ."

"In 'poetry,' or in 'poetic' language, one never really knows what is ever said or meant . . ."

"Poetry is never an empty vehicle or medium meant to deliver or communicate any message as such. Poetry is a medium; the medium is the message."

"The concept of an 'empty vehicle' is analogous to that of a 'transparent' medium, or one in which communication occurs THROUGH language rather than WITHIN language

itself . . . An 'empty' medium does not contain that which it communicates; a 'transparent' medium shows or displays that which is not THERE, but that which is on the OTHER side . . ."

"Poetic language should generally strive to be concrete, not abstract. This 'concreteness' is attained by 'words' being fully present as meaningful or significant 'things' in the composition of poetry, rather than 'words' becoming empty 'signs' of absent things or of otherwise abstract(ed) ideas . . ."

"All in all, I believe that the best poetry communicates virtually all of its meaning at its surface, its content in its form (or vice versa), and neither clarifies nor obscures whatever lies deep beneath or beyond. In this sense, the 'superficial' is actually very 'profound' indeed, if only

for those who truly wish to explore further . . ."

(gringocarioca)

Tuesday, September 05, 2006

On Seeing and the Imagination . . .

"the imagination . . . its true force lies in its marvellous insight and foresight, – that it is, instead of a false and deceptive faculty, exactly the most accurate and truth-telling faculty which the human mind possesses; and all the more truth-telling, because in its work, the vanity and individualism of the man himself are crushed, and he becomes a mere instrument or mirror, used by a higher power for the reflection to others of a truth which no effort of his could ever have ascertained; so that all mathematical, and arithmetical, and generally scientific truth, is, in comparison, truth of the husk and surface, hard and shallow; and only the imaginative truth is precious. Hence, whenever we want to know what are the chief facts of any case, it is better not to go to political economists, nor to mathematicians, but to the great poets; for I find they always see more of the matter than any one else . . ."

(John Ruskin, selections from Modern Painters)

Monday, September 04, 2006

"Ripple in still water . . ."

“There is a road, no simple highway,

Between the dawn and the dark of night,

And if you go no one may follow,

That path is for your steps alone . . .

You who choose to lead must follow,

But if you fall you fall alone,

If you should stand then who's to guide you?

If I knew the way I would take you home.”

(from “Ripple,” by Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter)

Wednesday, August 30, 2006

Devil's Blues

My friend Fred,

A luckless lad,

Hangs his head

So very sad,

Sings his songs

All black and blue –

What is wrong

Inside of you?

Silly Sally,

Such success,

Devil dares her

To undress –

Ho now, honey!

Rock and roll . . .

Makes her money,

Sells her soul

Why don´t you

Sing your song

So black and blue

To my friend Fred

And save his soul –

Right the wrongs

With rock and roll?

Hangs his head,

Sees silly Sally

Fall for my friend Fred –

They make much money,

Such success,

Live in love

And leave the rest

To me . . .

Copyright © 2002 Marco Alexandre de Oliveira

"Poets and Poems"

“Poetry, my dear friends, is a sacred incarnation of a smile. Poetry is a sigh that dries the tears. Poetry is a spirit who dwells in the soul, whose nourishment is the heart, whose wine is affection. Poetry that comes not in this form is a false messiah.

Oh spirits of the poets, who watch over us from the heaven of Eternity, we go to the alters you have adorned with the pearls of your thoughts and the gems of your souls because we are oppressed by the clang of steel and the clamor of factories. Therefore our poems are as heavy as freight trains and as annoying as steam whistles.

And you, the real poets, forgive us. We belong in the

(Kahlil Gibran, Thoughts and Meditations, Trans. Anthony R. Ferris)

Monday, August 28, 2006

On Cryptograms . . .

“Perhaps life needs to be deciphered like a cryptogram. Secret staircases, frames from which the paintings quickly slip aside and vanish (giving way to an archangel bearing a sword or to those who must forever advance), buttons which must be indirectly pressed to make an entire room move sideways or vertically, or immediately change all its furnishings; we may imagine the mind’s greatest adventure as a journey of this sort to the paradise of pitfalls”

(André Breton, Nadja, Trans. Richard Howard)

Sunday, August 27, 2006

"William Blake: Visionary and Illustrator"

"The Tyger"

(from Songs of Experience)

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes!

On what wings dare he aspire!

What the hand, dare sieze the fire?

And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

What the hammer? what the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? what dread grasp,

Dare its deadly terrors clasp!

When the stars threw down their spears

And water'd heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

Tyger, Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

Monday, August 21, 2006

Saturday, August 19, 2006

on the NARROW ROAD TO THE INTERIOR . . .

“The moon and sun are eternal travelers. Even the years wander on. A lifetime adrift in a boat, or in old age leading a tired horse into the years, every day is a journey, and the journey itself is home.”

"With every pilgrimage one encounters the temporality of life. To die along the road is destiny."

(Matsuo Basho,

Wednesday, August 16, 2006

On Contradiction(s) . . .

“‘A’ cannot be itself unless it stands against what is not ‘A’; ‘not-A’ is needed to make ‘A’ ‘A,’ which means that ‘not-A’ is in ‘A.’ When ‘A’ wants to be itself, it is already outside itself, that is, ‘not-A.’ If ‘A’ did not contain in itself what is not itself, ‘not-A’ could not come out of ‘A’ so as to make ‘A’ what it is. ‘A’ is ‘A’ because of this contradiction . . .”

(D. T. Suzuki, Zen Buddhism: Selected Writings of D. T. Suzuki)

Saturday, August 05, 2006

Song of Himself . . .

“Have you practiced so long to learn to read?

Have you felt so proud to get at the meaning of poems?

Stop this day and night with me and you shall possess the origin of all poems,

You shall possess the good of the earth and sun, (there are millions of suns left,)

You shall no longer take things at second or third hand, nor look through the

eyes of the dead, nor feed on the specters in books,

You shall not look through my eyes either, nor take things from me,

You shall listen to all sides and filter them from your self.”

. . .

“I have heard what the talkers were talking, the talk of the

beginning and the end,

But I do not talk of the beginning or the end.

There was never any more inception than there is now,

Nor any more youth or age than there is now,

And will never be any more perfection than there is now,

Nor any more heaven or hell than there is now.”

. . .

“These are really the thoughts of all men in all ages and lands,

they are not original with me,

If they are not yours as much as mine they are nothing, or

next to nothing,

If they are not the riddle and the untying of the riddle they

are nothing,

If they are not just as close as they are distant they are nothing.

This is the grass that grows wherever the land is and the water is,

This the common air that bathes the globe.”

. . .

“To me the converging objects of the universe perpetually flow,

All are written to me, and I must get what the writing means.”

. . .

“I exist as I am, that is enough,

If no other in the world be aware I sit content,

And if each and all be aware I sit content.

One world is aware and by far the largest to me, and that is myself,

And whether I come to my own to-day or in ten thousand or ten

million years,

I can cheerfully take it now, or with equal cheerfulness I can wait.

My foothold is tenoned and mortised in granite,

I laugh at what you call dissolution,

And I know the amplitude of time.”

. . .

“There is that in me - I do not know what it is - but I know it is in me.

Wrenched and sweaty - calm and cool then my body becomes,

I sleep - I sleep long.

I do not know it - it is without name - it is a word unsaid,

It is not in any dictionary, utterance, symbol.

Something it swings on more than the earth I swing on,

To it the creation is the friend whose embracing awakes me.

Perhaps I might tell more. Outlines! I plead for my brothers and sisters.

Do you see O my brothers and sisters?

It is not chaos or death - it is form, union, plan - it is eternal life - it is Happiness.”

. . .

“The past and present wilt - I have filled them, emptied them.

And proceed to fill my next fold of the future.

Listener up there! what have you to confide to me?

Look in my face while I snuff the sidle of evening,

(Talk honestly, no one else hears you, and I stay only a minute longer.)

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

I concentrate toward them that are nigh, I wait on the door-slab.

Who has done his day's work? who will soonest be through with his supper?

Who wishes to walk with me?

Will you speak before I am gone? will you prove already too late?”

(from Walt Whitman, "Song of Myself")

Sunday, July 30, 2006

Saturday, July 29, 2006

Monday, July 24, 2006

On Art and Illusion (again) . . .

“For the artist, too, cannot transcribe what he sees; he can only translate it into the terms of his medium.”

“Indeed, the true miracle of the language of art is not that it enables the artist to create the illusion of reality. It is that under the hands of a great master the image becomes translucent. In teaching us to see the visible world afresh, he gives us the illusion of looking into the invisible realms of the mind – if only we know . . . how to use our eyes.”

(E. H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion)

Saturday, July 22, 2006

Sunday, July 16, 2006

where you are is where you are not ? ! ?

“You say I am repeating

Something I have said before. I shall say it again.

Shall I say it again? In order to arrive there,

To arrive where you are, to get from where you are not,

You must go by a way wherein there is no ecstasy.

In order to arrive at what you do not know

You must go by a way which is the way of ignorance.

In order to possess what you do not possess

You must go by the way of dispossession.

In order to arrive at what you are not

You must go through the way in which you are not.

And what you do not know is the only thing you know

And what you own is what you do not own

And where you are is where you are not.”

(T.S. Eliot, “East Coker”)

Saturday, July 15, 2006

On Art and Illusion . . .

“Should we not say that we make a house by the art of building, and by the art of painting we make another house, a sort of man-made dream produced for those who are awake?”

(Plato, Sophist, quoted in E. H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion)

“Illusion . . . is hard to describe or analyze, for though we may be intellectually aware of the fact that any given experience must be an illusion, we cannot, strictly speaking, watch ourselves having an illusion.”

(E. H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion)

Friday, July 07, 2006

The Nature of Art ? ! ?

(Martin Heidegger, Poetry, Language, Thought)

Tuesday, July 04, 2006

from the Heart Sutra . . .

"Form is emptiness; emptiness also is form. Emptiness is no other than form; form is no other than emptiness. In the same way, feeling, perception, formation and consciousness are emptiness . . . There are no characteristics. There is no birth and no cessation. There is no impurity and no purity. There is no decrease and no increase. Therefore . . . in emptiness there is no form, no feeling, no perception, no formation, no consciousness; no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind; no appearance, no sound, no smell, no taste, no touch . . . no ignorance, no end of ignorance . . . no old age and death, no end of old age and death; no suffering, no origin of suffering, no cessation of suffering, no path, no wisdom, no attainment, and no non-attainment."

(Trans. Nalanda Translation Committee)

Saturday, June 24, 2006

A dream within a dream ?!?

“Once upon a time, I, Chuang Tzu, dreamt I was a butterfly, fluttering hither and thither, to all intents and purposes a butterfly. I was conscious only of following my fancies as a butterfly, and was unconscious of my individuality as a man. Suddenly, I awaked, and there I lay, myself again. Now I do not know whether I was then a man dreaming I was a butterfly, or whether I am now a butterfly, dreaming I am a man. Between a man and a butterfly there is necessarily a barrier. The transition is called Metempsychosis.”

(Chuang Tzu, Trans. Herbert A. Giles)

Sunday, June 18, 2006

Monday, June 12, 2006

Friday, June 02, 2006

Thursday, April 27, 2006

On Pudding and Machinery . . .

(W. K. Wimsatt, Jr.,"The Intentional Fallacy")

Tuesday, April 25, 2006

Love thy enemy ? ! ?

(Georg Lukáçs, "The Ideal of the Harmonious Man in Bourgeois Aesthetics")

Monday, April 17, 2006

being (de)void of being . . .

śūnyatā

– form is emptiness and emptiness is form –

reflections of the void

unfold

mirrors of the void

untold

voids unfold the untold voids

(non)

being becoming being

Copyright © 2006 Marco Alexandre de Oliveira

Thursday, April 13, 2006

The Essence of Poetry (Part 2)

“Existence is ‘poetical’ in its fundamental aspect . . . Poetry is not merely an ornament accompanying existence, not merely a temporary enthusiasm or nothing but an interest and amusement . . .That our existence is fundamentally poetic, this cannot in the last resort mean that it is really only a harmless game.”

“Poetry looks like a game and yet it is not. A game does indeed bring men together, but in such a way that each forgets himself in the process. In poetry on the other hand, man is reunited on the foundation of existence. There he comes to rest; not indeed to the seeming rest of inactivity and emptiness of thought, but to that infinite state of rest in which all powers and relations are active.”

“Poetry rouses the appearance of the unreal and of dream in the face of the palpable and clamorous reality, in which we believe ourselves at home. And yet in just the reverse manner, what the poet says and undertakes to be, is the real.”

(Martin Heidegger, “Hölderlin and the Essence of Poetry”)

The Essence of Poetry (Part 1)

“Language serves to give information. As a fit instrument for this, it is a ‘possession.’ But the essence of language does not consist entirely in being a means of giving information. This definition does not touch its essential essence, but merely indicates an effect of its essence. Language is not a mere tool, one of the many which man possesses; on the contrary, it is only language that affords the very possibility of standing in the openness of the existent. Only where there is language, is there world . . .”

“Poetry is the act of establishing by the word and in the word. What is established in this manner? The permanent . . . That which supports and dominates the existent in its entirety must become manifest. Being must be opened out, so that the existent may appear. But this very permanent is the transitory.”

“The poet names the gods and names all things in that which they are. This naming does not consist merely in something already known being supplied with a name; it is rather that when the poet speaks the essential word, the existent is by this naming nominated as what it is. So it becomes known as existent. Poetry is the establishing of being by means of the word.”

“Existence is ‘poetical’ in its fundamental aspect – which means at the same time: in so far as it is established (founded), it is not a recompense, but a gift.”

“the essence of poetry must be understood through the essence of language . . . the essence of language must be understood through the essence of poetry.”

(Martin Heidegger, “Hölderlin and the Essence of Poetry”)

Tuesday, April 11, 2006

Signs of the Times ? ! ?

“Some people regard language, when reduced to its elements, as a naming-process only – a list of words, each corresponding to the thing that it names . . . The linguistic sign unites, not a thing and a name, but a concept and a sound-image.”

“The bond between the signifier and the signified is arbitrary. Since I mean by sign the whole that results from the associating of the signifier with the signified, I can simple say: the linguistic sign is arbitrary.”

“The word arbitrary . . . should not imply that the choice of the signifier is left entirely to the speaker (we shall see below that the individual does not have the power to change a sign in any way once it has become established in the linguistic community); I mean that it is unmotivated, i.e. arbitrary in that it actually has no natural connection with the signified.”

“No matter what period we choose or how far back we go, language always appears as a heritage of the preceding period. We might conceive of an act by which, at a given moment, names were assigned to things and a contract was formed between concepts and sound-images; but such an act has never been recorded . . . the question of the origin of speech is not so important as it is generally assumed to be. The question is not even worth asking . . .”

“in language . . . everyone participates at all times, and that is why it is constantly being influenced by all. This capital fact suffices to show the impossibility of revolution. Of all social institutions, language is the least amenable to initiative. It blends with the life of society, and the latter, inert by nature, is a prime conservative force.”

“Because the sign is arbitrary, it follows no law other than tradition, and because it is based on tradition, it is arbitrary.”

(Ferdinand de Saussure, "Nature of the Linguistic Sign")

Sunday, April 09, 2006

Thursday, April 06, 2006

Transition and the Universal Talent

“if we approach a poet . . . we shall often find that not only the best, but the most individual parts of his work may be those in which the dead poets, his ancestors, assert their immortality most vigorously.”

“Tradition . . . cannot be inherited, and if you want it you must obtain it by great labour. It involves, in the first place, the historical sense . . . and the historical sense involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence; the historical sense . . . which is a sense of the timeless as well as of the temporal and of the timeless and of the temporal together, is what makes a writer traditional. And it is at the same time what makes a writer most acutely conscious of his place in time, of his contemporaneity.”

“No poet, no artist of any art, has his complete meaning alone. His significance, his appreciation is the appreciation of his relation to the dead poets and artists . . . what happens when a new work of art is created is something that happens simultaneously to all the works of art which preceded it. The existing monuments form an ideal order among themselves, which is modified by the introduction of the new (the really new) work of art among them. The existing order is complete before the new work arrives; for order to persist after the supervention of novelty, the whole existing order must be, if ever so slightly, altered; and so the relations, proportions, values of each work of art toward the whole are readjusted; and this is conformity between the old and the new. Whoever has approved this idea of order . . . will not find it preposterous that the past should be altered by the present as much as the present is directed by the past.”

“. . . But the difference between the present and the past is that the conscious present is an awareness of the past in a way and to an extent which the past's awareness of itself cannot show . . . What is to be insisted upon is that the poet must develop or procure the consciousness of the past and that he should continue to develop this consciousness throughout his career.

What happens is a continual surrender of himself as he is at the moment to something which is more valuable. The progress of an artist is a continual self-sacrifice, a continual extinction of personality.”

“I shall, therefore, invite you to consider, as a suggestive analogy, the action which takes place when a bit of finely filiated platinum is introduced into a chamber containing oxygen and sulphur dioxide.”

(T.S. Eliot, “Tradition and the Individual Talent”)

.bmp)

.gif)

.gif)