Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Sunday, November 26, 2006

poetree

bears a tree with bare branches stems from parched bark and twisted twigs leaves fallen leaves to winter wind roots the sky in dry earth sprouts within and blooms without flowers the seeds of trees . . .

Copyright © 2006 Marco Alexandre de Oliveira

On the Edge of Happiness . . .

“It was his fate, his peculiarity, whether he wished it or not, to come out thus on a spit of land which the sea is slowly eating away, and there to stand, like a desolate sea-bird, alone. It was his power, his gift, suddenly to shed all superfluities, to shrink and diminish so that he looked barer and felt sparer, even physically, yet lost none of his intensity of mind, and so to stand on his little ledge facing the dark of human ignorance, how we know nothing and the sea eats away the ground we stand on – that was his fate, his gift.”

“He turned from the sight of human ignorance and human fate and the sea eating the ground we stand on, which, had he been able to contemplate it fixedly might have led to something; and found consolation in trifles so slight compared with the august theme just now before him that he was disposed to slur the comfort over, to deprecate it, as if to be caught happy in a world of misery was for an honest man the most despicable of crimes. It was true; he was for the most part happy. . . .”

(Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse)

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

A Time to Rhyme

only herds

of lonely words –

a faceless multitude,

a baseless solitude –

traverse in verse

the pages of the ages.

names in frames – like you and I – as real and ideal as earth and sky, wander around and wonder about the signs they signify, or the nature of their stature, from their birth until they die; for still the years still transform begotten forms until appearances disappear along with long forgotten formal norms of characterization, characterized by characters in action . . . of course, perhaps this so-called individual discourse, per se, after all never original, is always and ever a source of hype, a perverse type of blend adverse to trends and style; while meanwhile seen as a genius of a genus, is such, as such, in a sense, in essence, a nonsense, since this revolution of resolution is the expression of impressions of the same rules from whence it came; hence fools become tools of a tragic logic as subjects object to a language of bondage: “objects subject to the bondage of language!” the former insists, the latter resists – letters in fetters digress, impede progress – the stampede tramples over borders of thought, these orders that ought to contain and restrain remain what sustain a predestined ambition: to end and transcend a questioned condition, a unique and oblique obsession reflective of a perspective of oppression . . . finally a finale – herds of words are heard! a leader elects to select a reader to free the story from history, and (re)present the advent of the moment, to see all class as allegory, and pass the time(s) with rhyme(s). . . .

Copyright © 2006 Marco Alexandre de Oliveira

On Sesame and Lilies . . .

“And be sure also, if the writer is worth anything, that you will not get at his meaning all at once; – nay, that at his whole meaning you will not for a long time arrive in any wise. Not that he does not say what he means, and in strong words too; but he cannot say it all; and what is more strange, will not, but in a hidden way and in parables, in order that he may be sure you want it. I cannot quite see the reason of this, nor analyze that cruel reticence in the breasts of wise men which makes them always hide their deeper thought. They do not give it you by way of help, but of reward; and will make themselves sure that you deserve it before they allow you to reach it. . . ."

(John Ruskin, Sesame and Lilies)

Saturday, November 18, 2006

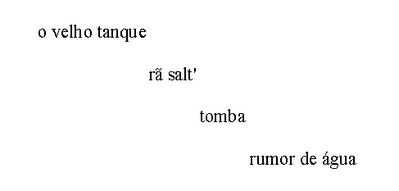

Velha lagoa / Old pond . . .

O velho tanque / The old pond . . .

Thursday, November 16, 2006

Impressions on Art . . .

“And what other means were open to me than the creation of a work of art?”

“Thus I had already reached the conclusion that we are in no wise free in the presence of a work of art, that we do not create it as we please but that it pre-exists in us and we are compelled as though it were a law of nature to discover it because it is at once hidden from us and necessary. But is not that discovery, which art may enable us to make, most precious to us, a discovery of that which for most of us remains for ever unknown, our true life, reality as we have ourselves felt it and which differs so much from that which we had believed that we are filled with delight when chance brings us an authentic revelation of it?”

“The grandeur of veritable art . . . is to recapture, to lay hold of, to make one with ourselves that reality far removed from the one we live in, from which we separate ourselves more and more as the knowledge which we substitute for it acquires a greater solidity and impermeability, a reality we run the risk of never knowing before we die but which is our real, our true life at last revealed and illumined, the only life which is really lived and which in one sense lives at every moment in all men as well as in the artist. But they do not see it because they do not seek to illuminate it. And thus their past is encumbered with innumerable “negatives” which remain useless because the intelligence has not “developed” them. To lay hold of our life; and also the life of others; for a writer’s style and also a painter’s are matters not of technique but of vision. It is the revelation, impossible by direct and conscious means, of the qualitative difference there is in the way in which we look at the world, a difference which, without art, would remain for ever each man’s personal secret. By art alone we are able to get outside ourselves, to know what another sees of this universe which for him is not ours, the landscapes of which would remain as unknown to us as those of the moon. Thanks to art, instead of seeing one world, our own, we see it multiplied and as many original artists as there are, so many worlds are at our disposal, differing more widely from each other than those which roll round the infinite and which . . . send us their unique rays many centuries after the hearth from which they emanate is extinguished. This labour of the artist to discover a means of apprehending beneath matter and experience, beneath words, something different from their appearance . . . this complex art is precisely the only living art. It alone expresses for others and makes us see, our own life, that life which cannot observe itself, the outer forms of which, when observed, need to be interpreted and often read upside down, in order to be laboriously deciphered.”

Marcel Proust, Time Regained (Vol. 7 of Remembrance of Things Past. Trans. Stephen Hudson)

A Book of Symbols . . .

“I was attempting to concentrate my mind on a compelling image, a cloud, a triangle, a belfry, a flower, a pebble, believing that there was perhaps something else under those symbols I ought to try to discover, a thought which these objects were expressing in the manner of hieroglyphic characters which one might imagine only represented material objects. Doubtless such deciphering was difficult, but it alone could yield some part of the truth.”

“That book of unknown signs within me (signs in relief it seemed, for my concentrated attention, as it explored my unconscious in its search, struck against them, circled round them like a diver sounding) no one could help me read by any rule, for its reading consists in an act of creation in which no one can take our place and in which no one can collaborate . . . That book which is the most arduous of all to decipher is the only one which reality has dictated, the only one printed within us by reality itself. Whatever idea life has left in us, its material shape, mark of the impression it has made on us, is still the necessary pledge of its truth . . . Our only book is that one not made by ourselves whose characters are already imaged . . . That which we have not been forced to decipher, to clarify by our own personal effort, that which was made clear before, is not ours. Only that issues from ourselves which we ourselves extract from the darkness within ourselves and which is unknown to others. And as art exactly recomposes life, an atmosphere of poetry surrounds those truths within ourselves to which we attain, the sweetness of a mystery which is but the twilight through which we have passed.”

“I perceived that to express those impressions, to write that essential book, which as the only true one, a great writer does not, in the current meaning of the word, invent it, but, since it exists already in each one of us, interprets it. The duty and the task of a writer are those of an interpreter.”

Marcel Proust, Time Regained (Vol. 7 of Remembrance of Things Past. Trans. Stephen Hudson)

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

Doors to Nowhere . . .

“But it is sometimes just at the moment when we think that everything is lost that the intimation arrives which may save us; one has knocked at all the doors which lead nowhere, and then one stumbles without knowing it on the only door through which one can enter – which one might have sought in vain for a hundred years – and it opens of its own accord.”

Marcel Proust, Time Regained. (Vol. 7 of Remembrance of Things Past. Trans. Moncrieff and Kilmartin)

Monday, November 13, 2006

In Search of Lost Hope . . .

"How often . . . did I reflect on my lack of qualification for a literary career, and that I must abandon all hope of ever becoming a famous author. The regret that I felt for this, while I lingered alone to dream for a little by myself, made me suffer so acutely that, in order not to feel it, my mind of its own accord, by a sort of inhibition in the instant of pain, ceased entirely to think of verse-making, of fiction, of the poetic future on which my want of talent precluded me from counting. Then, quite apart from all those literary preoccupations, and without definite attachment to anything, suddenly a roof, a gleam of sunlight reflected from a stone, the smell of a road would make me stop still, to enjoy the special pleasure that each of them gave me, and also because they appeared to be concealing, beneath what my eyes could see, something which they invited me to approach and seize from them, but which, despite all my efforts, I never managed to discover. As I felt that the mysterious object was to be found in them, I would stand there in front of them, motionless, gazing, breathing, endeavouring to penetrate with my mind beyond the thing seen or smelt. And if I had then . . . to proceed on my way, I would still seek to recover my sense of them by closing my eyes; I would concentrate upon recalling exactly the line of the roof, the colour of the stone, which, without my being able to understand why, had seemed to me to be teeming, ready to open, to yield up to me the secret treasure of which they were themselves no more than the outer coverings. It was certainly not any impression of this kind that could or would restore the hope I had lost of succeeding one day in becoming an author and poet, for each of them was associated with some material object devoid of any intellectual value, and suggesting no abstract truth. But at least they gave me an unreasoning pleasure, the illusion of a sort of fecundity of mind; and in that way distracted me from the tedium, from the sense of my own impotence which I had felt whenever I had sought a philosophic theme for some great literary work . . . ."

[Swann's Way (Vol. 1 of Remembrance of Things Past) by Marcel Proust, translated from the French by C. K. Scott Moncrieff (1922)]

http://www.authorama.com/remembrance-of-things-past-4.html

Thursday, November 09, 2006

Tuesday, November 07, 2006

ut pictura poesis

ver no poema o que dizer na pintura

da figura a compor:

o inverso do universo em verso

Copyright © 2006 Marco Alexandre de Oliveira

Sunday, November 05, 2006

On Reading (Proust) . . .

“And then my thoughts, did not they form a similar sort of hiding-hole, in the depths of which I felt that I could bury myself and remain invisible even when I was looking at what went on outside? When I saw any external object, my consciousness that I was seeing it would remain between me and it, enclosing it in a slender, incorporeal outline which prevented me from ever coming directly in contact with the material form; for it would volatilise itself in some way before I could touch it . . . Upon the sort of screen, patterned with different states and impressions, which my consciousness would quietly unfold while I was reading, and which ranged from the most deeply hidden aspirations of my heart to the wholly external view of the horizon spread out before my eyes at the foot of the garden, what was from the first the most permanent and the most intimate part of me, the lever whose incessant movements controlled all the rest, was my belief in the philosophic richness and beauty of the book I was reading, and my desire to appropriate these to myself, whatever the book might be. For even if I had purchased it . . . I should have noticed and bought it there simply because I had recognised it as a book which had been well spoken of, in my hearing, by the school-master or the school-friend who, at that particular time, seemed to me to be entrusted with the secret of Truth and Beauty, things half-felt by me, half-incomprehensible, the full understanding of which was the vague but permanent object of my thoughts.”

“Next to this central belief, which, while I was reading, would be constantly a motion from my inner self to the outer world, towards the discovery of Truth, came the emotions aroused in me by the action in which I would be taking part, for these afternoons were crammed with more dramatic and sensational events than occur, often, in a whole lifetime. These were the events which took place in the book I was reading . . .But none of the feelings which the joys or misfortunes of a ‘real’ person awaken in us can be awakened except through a mental picture of those joys or misfortunes; and the ingenuity of the first novelist lay in his understanding that, as the picture was the one essential element in the complicated structure of our emotions, so that simplification of it which consisted in the suppression, pure and simple, of ‘real’ people would be a decided improvement. A ‘real’ person, profoundly as we may sympathise with him, is in a great measure perceptible only through our senses, that is to say, he remains opaque, offers a dead weight which our sensibilities have not the strength to lift . . .The novelist’s happy discovery was to think of substituting for those opaque sections, impenetrable by the human spirit, their equivalent in immaterial sections, things, that is, which the spirit can assimilate to itself. After which it matters not that the actions, the feelings of this new order of creatures appear to us in the guise of truth, since we have made them our own, since it is in ourselves that they are happening, that they are holding in thrall, while we turn over, feverishly, the pages of the book, our quickened breath and staring eyes. And once the novelist has brought us to that state, in which, as in all purely mental states, every emotion is multiplied ten-fold, into which his book comes to disturb us as might a dream, but a dream more lucid, and of a more lasting impression than those which come to us in sleep; why, then, for the space of an hour he sets free within us all the joys and sorrows in the world, a few of which, only, we should have to spend years of our actual life in getting to know, and the keenest, the most intense of which would never have been revealed to us because the slow course of their development stops our perception of them. It is the same in life; the heart changes, and that is our worst misfortune; but we learn of it only from reading or by imagination; for in reality its alteration, like that of certain natural phenomena, is so gradual that, even if we are able to distinguish, successively, each of its different states, we are still spared the actual sensation of change.”

“Had my parents allowed me, when I read a book, to pay a visit to the country it described, I should have felt that I was making an enormous advance towards the ultimate conquest of truth. For even if we have the sensation of being always enveloped in, surrounded by our own soul, still it does not seem a fixed and immovable prison; rather do we seem to be borne away with it, and perpetually struggling to pass beyond it, to break out into the world, with a perpetual discouragement as we hear endlessly, all around us, that unvarying sound which is no echo from without, but the resonance of a vibration from within. We try to discover in things, endeared to us on that account, the spiritual glamour which we ourselves have cast upon them; we are disillusioned, and learn that they are in themselves barren and devoid of the charm which they owed, in our minds, to the association of certain ideas; sometimes we mobilise all our spiritual forces in a glittering array so as to influence and subjugate other human beings who, as we very well know, are situated outside ourselves, where we can never reach them . . . .”

[Swann's Way (Vol. 1 of Remembrance of Things Past) by Marcel Proust, translated from the French by C. K. Scott Moncrieff (1922)]

.bmp)